In our beloved wine country, the old and new alike venture in search of the perfect vineyard across the Southern line. However as suitable land is becoming scarcer and land prices continue to climb, is planting the future for the UK wine industry? Well, perhaps not.

Wines of Great Britain reports in 2019 a 24% increase in the overall land now under vine, with an estimated three million vines going in the ground this year alone. This brings the total hectarage up from 2,888 to just over 3,500 hectares.

In 2018’s bumper harvest, capacity issues were seen where there was no remaining tank space for vintage demands. While this anomaly maybe due to the perfect storm of 2018, it could become more of a common occurrence in future years, due to climate change and more established vineyards coming online.

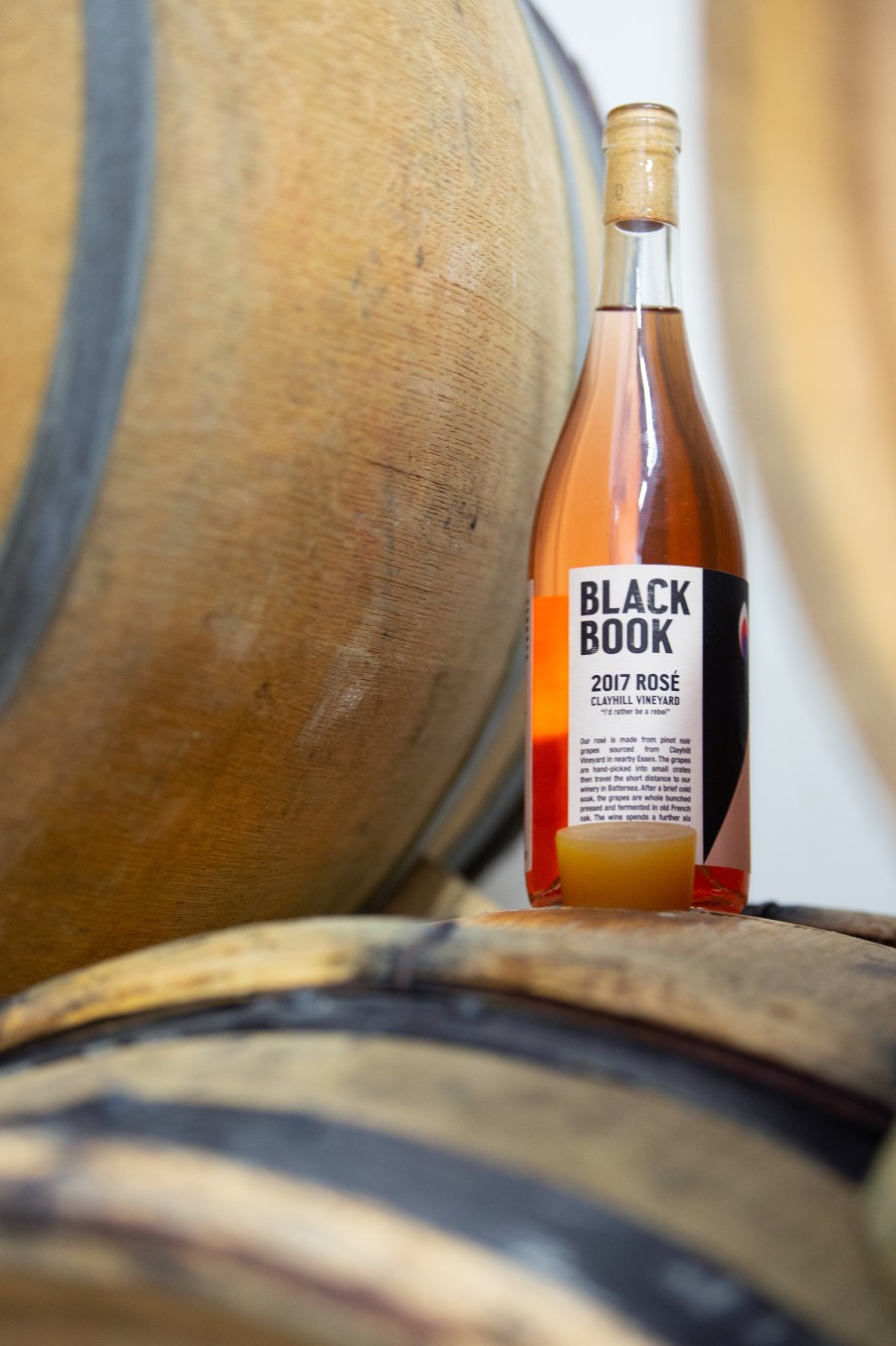

As the market for grapes continues to mature, and grow, it is logical that more producers may opt, as we have at Blackbook, to bypass the decision to plant and instead focus on developing relationships with trusted growers to source our fruit.

For decades, even centuries, wineries around the world have adapted to changing conditions through the ability to purchase fruit from different sites, some locally and others further afield to make their wine. Those whose production is from 100% purchased fruit can be described as a négociant – a winery who buys grapes, or grape juice, from others and sells the wine under their own name.

In recent years many have preferred to use this model; often the younger generations marked as New Wavers. No better example can be seen than in South Africa, where a group of likeminded individuals are seeking forgotten vineyards and varieties lost in the fog of Chenin blanc, Pinotage and Chardonnay. Take for example, Blankbottle, Craven Wines and Savage Wines.

Beyond the romance of the New Wavers, a good example is Burgundy as an epi-centre for micro-negoc due to the prohibitive cost of land – vineyards can cost upwards of millions for a sliver of a 1er cru or Grand Cru plot; Le Grappin is a key example known well to the UK market.

While both arable land and established vineyards in the UK are nowhere near the inflated prices of Burgundy and its neighbours, a commercial planting could set you back between £15,000-£25,000 per acre for land and planting. But it is not just the establishment. There is the yearly running cost of anywhere between £5,000-£10,000 per acre, plus the three to four year waiting time. The initial outlay and waiting, ultimately ends up with at least a 10-year timeline to see any return. Dreams of transplanting the south of France to the sunny hills of the English countryside could end in tears.

For us, grape purchasing may be the answer. As well as offering a more accessible route to starting a label, grape purchasing enables the producer to source a diverse selection of varieties, adjust the mix over time according to desire and demand, and shift the production size up and down.

As a producer, grape-buying means not being tied down to a specific site. I am able to source fruit from Sussex, Kent, Essex and beyond, highlighting the immensely diverse micro climates within each of those sites. In some cases, finding lost plots and working to revitalise them.

As a micro-negoc, there is no need to wait four years (for still wine, sparkling is an eternity of a wait!) before seeing a return on one’s investment. Conceptually, wine is being sold earlier therefore income is received earlier. The earlier returns lead to a reduced time towards profitability making the whole project more viable for a start-up.

There is a third scenario here. The option to lease vineyards. I believe this could be a good alternative for the control freaks out there (I include myself in this grouping). The capital outlay is much lower than planting, but the direction of the vineyard is under direction by Leasee who rents the site, as is the cost of maintaining the site. This is a good alternative, but I feel the same can be achieved with the right grower relationship.

As the UK rises through the ranks of growth, would more businesses want to be a négociant? At the moment, in the current state of affairs, I would say yes. As years continue, vines are coming of age, more fruit is hitting the open market and by extension more wine. My question is where will it all go?