2023 will undoubtedly be remembered as a near perfect year. There was little spring frost, text-book flowering weather in June and, after a generally wet and often dull summer (July and August), some very warm spells in September and October brought ripening on and most vineyards picked very large crops in good condition. Whilst crops were large, ripeness levels were lower than average, fine for sparkling wines, but not so good for still wines, although acids were lower than average, fine for still wines, but not so good for sparkling! The British climate always has a surprise to spring on vineyard owners.

Weather conditions for the year

The year started mildly with almost no frost and snow anywhere in Great Britain, and from the last week of January to the first week of March there was little in the way of rain in the southeast of the country. March started with some very cold days and nights and as the month proceeded, it became wetter and wetter with some parts of the country having much more than their usual rainfall. Cambridgeshire, usually a dry county, recorded 99mm of rain for the month, three times its average. England as a whole had twice the LTA (1991-2020 Long Term Average) rainfall for March, making it one of the wettest ever recorded. As April finished and May started, the wet weather continued, making planting new vines problematic and some new vineyards did not get planted until mid-June.

As May turned into June, the weather picked up and between 30 May and 30 June, temperatures of up to 32°C were recorded in some regions. The five days between 10 and 14 June all reached 30°C or higher, with 32.2°C being recorded on the 12 June. June 2023, with an average temperature of 15.8°C (2.5°C above the LTA), was the warmest June since records began to be collected in 1884 and almost a full 1°C warmer than 1940, the previous June record holder. This warm weather enabled flowering to get going on good sites and many varieties flowered between the 13 and 20 June, right in the middle of the hot spell. In general flowering went very well, with the warm weather in the middle of June allowing the rachis of the bunches to elongate and expand, something which goes some way to explain the above average bunch weights and heavy crops in many vineyards. This was the same as we saw in 2018, a record-breaking year, and 2023 looked like being another record-breaker. On later sites, there was some coulure and millerandage, which had the opposite effect and reduced yields.

The summer continued in stop-start mode, and whilst the southern half of Europe fried and in some places caught fire, July in Britain was generally cool with plenty of rain in some parts. August wasn’t much better and whilst a bit drier than July, was just as cool and nowhere in the country did the temperature rise above 30°C. As August turned into September the weather brightened up and despite some rain at the end of August, the beginning of September saw much higher temperatures, culminating with the highest temperature of the year on 10 September at Brogdale, near Faversham in Kent where 33.5°C was recorded. In the seven days between 4 and 10 September, somewhere in GB achieved a temperature of 30°C or higher, something that has only been seen in four previous Septembers. This mini-heatwave, which lasted until around the middle of the month, brought the grapes on and by the 16 September, all regions reported picking, albeit on early varieties and those with lighter crops. Storm Agnes swept in at the end of the month and brought quite a bit of wet and windy weather, although by the time it had reached the south and east of the country, its strength had diminished. September turned out to be one of the very warmest months since records began in 1884 (matched only by 2006) with an average temperature of 15.2°C, a full 2.2°C (or 17%) above the 1991-2020 LTA.

Picking of the major varieties in the larger regions (and where the crops were heaviest) didn’t really get going until the beginning of October and continued for the first three weeks of the month. Some growers waited for sugar levels to rise as they were quite low when sampling started two to three weeks before the anticipated harvest dates and they hoped that by hanging on, these levels would rise. In fact they probably did rise but were in turn diluted by the rain which started around 13 October and then didn’t really stop until well after harvesting finished. The first ten days of October were glorious with 26.1°C being recorded on 11 October at East Malling, Kent, a full 8°C above normal. However, October as a whole was one of the wettest on record with England receiving 140% of normal average rainfall, the seventh wettest October on record. The majority of grapes were picked by the end of the second week of October in the West region and the third week of October in the South East. For later varieties and later sites, picking continued throughout October and into November with the latest harvest date recorded by the survey as being 26 November.

Growing Degree Days (April to October) across seven sites in Essex, Kent, the Sussexes, Hampshire, and Somerset averaged 1,017 which is just about the same as the average across the same sites for 2018-22, although almost 10% lower than was recorded in 2022.

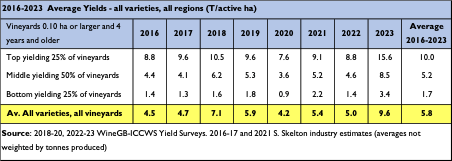

Yields

Yields in 2023 were very high, undoubtedly the highest ever recorded in the history of modern viticulture in Great Britain. As we saw in 2018, the previous record-holder, an absence of spring frosts and ideal flowering weather are the keys to large yields. For the top 25 per cent of vineyards to record an average across all varieties of 15.60 tonnes-ha (6.31 tonnes-acre), which is almost 50% higher than the previous record year (2018) is quite remarkable and double what is generally considered to be an economically sustainable yield for vineyards in GB. Even the lowest yielding vineyards managed 3.4 tonnes-ha (1.38 tonnes-acre), which is over twice their 2016-22 average yield. Chapel Down, GB’s largest producer, picked 3,811 tonnes off 304-ha, a yield of 12.54 tonnes-ha (5.07 tonnes-acre). To obtain this level of cropping over such a large area is a remarkable effort. Several exceptional growers averaged yields of 15.5 tonnes-ha (6.27 tonnes-acre) across a spread of varieties and sites.

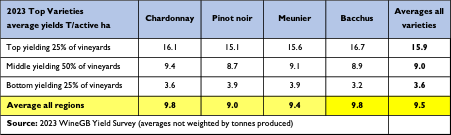

As might be expected in this year of miracles, the top four varieties, which account for almost 76% of the GB planted area (Wine Standards [WS] March 2023), performed amazingly well with the average of all vineyards almost reaching 10 tonnes-ha The top quartile exceeded all estimates with an average across the four varieties reaching 15.9 tonnes-ha (6.43 tonnes-acre). Such was the size of the crop, that even the bottom quartile produced twice its normal yield.

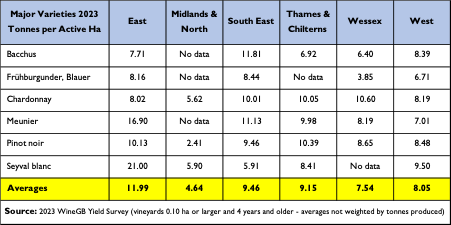

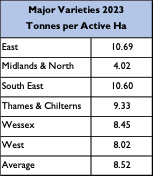

Yields by region show considerable variation

As has been seen in previous years, yields varied considerably in the different regions of GB. Top region in 2023 was East Anglia, whose figures were bolstered by stellar performances from some Meunier and Seyval blanc, with the South East coming in second. If you look at the top four varieties only, East Anglia and the South East are marginally ahead of the pack, with the other three major regions producing lower, but still respectable yields. The Midlands and North, which grow a much wider spectrum of varieties than other regions including PIWIs and higher yielding minor varieties, performed much less well. This is undoubtedly due to a later flowering which took place in less-clement weather than the more southerly parts of the country.

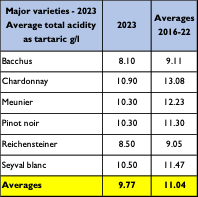

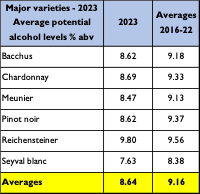

Sugar and acid levels

Apart from the much higher than normal yields, the other unusual factors in 2023 were the sugar and acid levels of the grapes. Taking the six major varieties, for which we have reasonable data from all regions, the average levels of potential alcohol in percentage alcohol by volume (abv) were down by just over 0.50% abv, not huge, but showing a definite trend towards lower sugar levels and therefore less-ripe grapes. The reason for this dip in sugar levels was undoubtedly a combination of the high yields and the rainfall during harvest in some vineyards.

Acidity levels on the other hand, which usually stubbornly hold up in years with heavy crops and a late-ish, cool harvest, were down by almost a full gramme per litre from the average, something rarely seen in GB vineyards. This was undoubtedly due to the wet weather, with grapes swelling and soaking up the rain in the early part of the harvest. A huge crop of course, takes time to pick and process, so allowing the grapes to hang longer than normal. What these two factors mean in terms of quality and longevity of the wines is, at this stage, something of an unknown, although winemakers are all saying that they are happy with their wines.

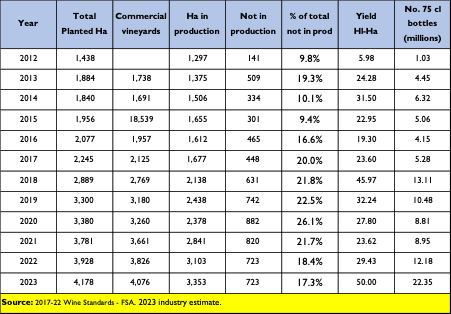

Future production of wine in GB

Yields over the years have risen both because of more and more vines being planted, as well as higher yields. The planted area has risen from 1,438-ha in 2012 to 4,178-ha in 2023 , an almost trebling of the vineyard area . If this level of increase in plantings were to continue, GB would have around 8,500-ha by 2030 with annual yields nearer to 40 million 75 cl bottles. The average yields per hectare have also been rising, but not in a straight line. Large variability in annual yields is a fact of life in vineyards in all countries and probably more-so in marginal regions. The average yields per hectare over the last ten years (2014-23), including a conservative estimate for 2023, is 30.64 hectolitre per hectare (hl-ha), whilst for the previous ten years (2004-13) it was 20.70 hl-ha, a rise of 48%. This is due to several factors: the climate which continues to surprise with the GDDs rising all the time, plus better sited and better planted vineyards (higher vine densities), and better vine husbandry.

Note: The data this report is based upon was collected via a voluntary survey to which 127 vineyard owners responded. Between them these producers grow 1,870-ha of vines with 1,640-ha of four year’s old or more and therefore in full production. This is around 50% of the anticipated national cropping area for 2023. It would be good to see more data from more growers, plus a little more data from Wales and the Midlands & North regions.