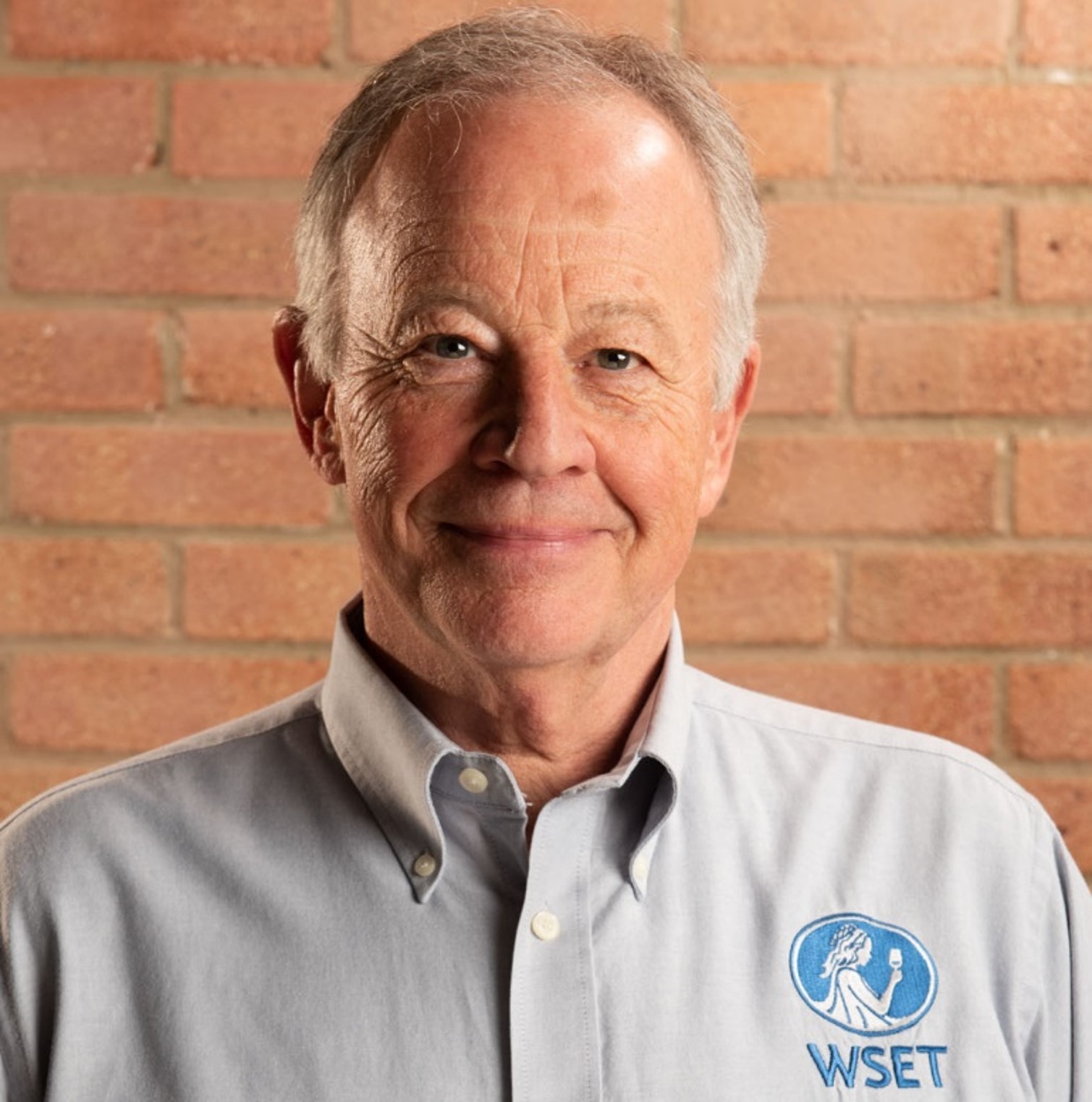

The retiring head of the Wine & Spirits Education Trust, Ian Harris gives a valedictory message: Education, education, education.

I officially joined WSET as ‘Chief Executive Designate’ on Monday 15 April 2002 – and on Friday 15 April 2022 – exactly 20 years later, my WSET journey comes to an end.

Prior to WSET, I was in the ‘mainstream’ of the industry – 10 years with Waverley Vintners (having started in their fine wine division: Christopher and Company in 1977), and then 15 years with Seagram, at that time the 4th biggest multinational in the wine and spirits industry.

Both Waverley and Seagram no longer exist (nothing to do with me, honest!) but I am delighted to report that WSET goes from strength to strength, in spite of everything the past two years have thrown at us.

Much has changed since my ‘lightbulb’ moment in 1975, in a Sauternes Vineyard when I decided that the wine ‘trade’ was what I wanted to do after university, thus sparking a career spanning 45 years.

One major change is the process of securing employment – in 1977, one speculative letter to the MD of Christopher & Company resulted in one interview, at the end of which I was offered a job. How different and difficult the job market is in 2022. (Then again, I was paid a pittance in my first job, as the wine trade was renowned for employing people who didn’t need the money!)

In my first month at Christopher’s, my new boss put me onto my first WSET course – the Certificate course. This was 1977, and my first contact with the organisation which was to become my life from 2002 onwards. I passed the Certificate, then the Higher Certificate in 1978 and the Diploma in 1980 (having failed the first part in 1979, but don’t tell anyone), and the syllabus at that time was virtually 100% ‘old world’.

Recently I found a presentation I had prepared for our stand at one of the very first London Wine Fairs in 1984, and this showed that the UK wine market was dominated by Europe, with French wines having over 40% share of the market, and the UK consumer’s appetite for German wines, although starting to decline, was still a major factor, with Germany having an impressive 29% share. Italy was No.3 with a share of 15%. My presentation didn’t show which producing countries made up the remaining 16% but Lutomer Riesling and Mateus Rose were still the choice of many UK wine drinkers! Australia and New Zealand were only just starting to make an impression in the 1980s (thanks to the foresight of ‘cutting-edge’ retailers such as Oddbins) and what about English Wines? Sadly (but perhaps justifiably at the time) no-one took them seriously.

Certainly, grape varieties such as Hexelrebe, Bacchus, Dornfelder and even Muller-Thurgau failed to excite at a time when the UK consumer was starting to recognise (and make their choices, based on) grape varieties.

Traditional wine merchants were focused entirely on the wines of Europe, and I remember a ‘token gesture’ of one Australian wine (Ch Tahbilk) one English Wine (Lamberhurst) and even a wine from China (Great Wall) tucked away in the back pages of the first price list when I started in the industry in 1977.

A holiday in California in 1986 – where I visited Napa and Sonoma, thanks to introductions from the Export Director of Robert Mondavi – was my first real insight into a world outside Europe, and my eyes were really opened to the ‘New World’ in 1987. Seagram UK were the UK distributors for the fledgling brands of Wolf Blass (Australia) and Montana (now Brancott, New Zealand), and I was responsible for Peter Dominic and Bottoms Up – names which have long since disappeared from the UK High St.

When I joined the Marketing team in the early 90s, I remember heated meetings with my Seagram colleagues at our Bordeaux negociant and producer in France when I showed them Wolf Blass Cabernet Sauvignon and Montana Sauvignon Blanc as examples of what the UK consumer was expecting from a wine at a price-point of £4.99!

Fast forward to the new millennium..

Even when I joined WSET as CEO in 2002, France was still providing the UK with 27% of its consumption (down from 40% in the early 1980s), but Germany had plummeted to a share of below 10% (down from 29% in the early 1980s) with Italy clinging on to a share of 12%. Australia had posted the most impressive growth – from a share of 0.1% in 1980, to over 17% in 2000. In the final two years of the last millennium, this represented an annual growth of over 20%. This growth rate was also mirrored by other ‘New World’ markets (New Zealand, Chile and even Argentina) – although South Africa had slowed down, although still growing in double-digits year-on-year. (Source of these stats: Seagram UK).

So, when I joined WSET, I was disappointed to find that the New World still had a tiny proportion of the syllabus at all Levels (Certificate, Higher Certificate and Diploma) and my initial questions were met with the response that “the ‘New World’ was all about big brands, and uninteresting wines, which students didn’t want or need to understand”.

So… priority No.1 was to bring the WSET syllabus up to date to reflect the 2002 market, (noting that 75% of WSET students at that time were in the UK). Today’s WSET students not only study a syllabus at all levels which reflects the current market, but they also learn about the commercial factors which influence the market.

Back in 2002, priority No.2 was to convince the industry that education was good for their business.

I was, by this point, no longer using the words wine ‘trade’, as this reminded me of the rather elitist culture when I first started working in 1977 – to me, we were all working in an ‘industry’, which started with the raw material which went into making a wine or a spirit and ended with the consumer purchasing a wine or spirit for consumption. The ‘industry’ therefore comprised every step of the supply chain and every person within it, and every company within every sector of that supply chain stood to gain if the consumer could be convinced to spend more on a glass, or a bottle, of wine or spirit.

My message was clear: the more the consumer (and the person at point of purchase) knew about the product, the more the consumer would be prepared to pay, and this increased margin would benefit every company up and down the supply chain in an industry which was struggling to turn even a small profit given the market conditions, not just in the UK but throughout the world. I argued that ‘Education’ (and WSET education in particular, obviously) should be seen as an integral part of the marketing mix.

It is therefore very satisfying to see virtually all generic bodies placing a high focus on educating the consumer – my message was hitting home!

By 2006, more than half of WSET’s students were based outside the UK, so the next priority was to convince producers in the major wine-producing countries that a knowledge of the global industry was key to their success. No longer could a producer in Bordeaux, Burgundy or Tuscany think of their competitors as the property down the road – competition was now coming from the other side of the world.

In my archive of market data, I have unearthed a presentation from Vinexpo from that time (the mid 2000s) with data provided by IWSR and GDR, which showed total wine consumption in the UK still rising in volume, and rising even higher in value, so maybe this was a sign that the power of education in the wine industry – and the market we all serve – was taking effect.

The figures from 2010 to 2020 (with grateful thanks to IWSR) show that the volume of wine consumed in the UK continues on a slight downward trend, but the value has grown by 20%. I know that WSET has played its part in helping the UK consumer to drink better and – although still a fledgling part of the industry – so has the UK wine industry. The growth and reputation of wines produced in this ‘Green and Pleasant Land’ (that’s the UK for anyone who doesn’t know William Blake’s famous poem) continue to show that £30+ for a bottle of English fizz is a perfectly fair price for a wine which is growing in stature and in quality. My best wishes to all who are involved in UK wine production – and it’s not just about global warming, it’s about grabbing the opportunity – something which I told my WSET team we could do two decades ago.

So now, as I approach the end of my 20 year journey at WSET, I am stepping down from leading a wonderful organisation which educated 108,584 students in the last financial and academic year – the highest ever in WSET’s history, in spite of Covid-19 and a suspension of WSET’s business in China for the final six months of the year. My sincere thanks to the wonderful team at WSET, as well as the ‘extended family’ of thousands of WSET educators in the 70+ countries where WSET programs are now available – a far cry from the UK-centric WSET of two decades ago.

It is a time of mixed emotions for me, but the wine industry is a bit like ‘Hotel California’, and again for those who don’t know the Eagles’ hit, my retirement from WSET is a bit like the line from that song: “you can check out any time you like, but you can never leave”.

I will never be able to leave.

Ian Harris at his investiture with the Queen

WSET class