Winter pruning is one of the most technical, expensive, and important tasks in the vineyard year. Vineyard finds out how pruning methods can help avoid potential yield losses from frost, disease, and poor weather at flowering.

Achieving vine balance, with the correct crop load and bud numbers is critical for managing the vine during the season, but in a cool climate even a healthy, well-pruned vine can have its potential yield ruined by frost, poor flowering and fruit set, or disease. A few adjustments, techniques and treatments during winter pruning can help in the battle against these obstacles.

Delayed pruning

There are many published studies that show delaying pruning will delay budburst and, thus, delay flowering to a time when the weather conditions are likely to be warmer and more favourable. “At Plumpton College we have had three students looking at delayed pruning in a UK vineyard,” explained Dr Greg Dunn, Head of Wine, “but so far we haven’t seen any delay in bud burst. This may be related to the UK climate and more work needs to be done specifically in the UK. In other countries delayed pruning has increased yield, as both flowering and bud differentiation occur during periods when the weather is likely to be better and warmer,” Greg continued.

“Delayed pruning could also be useful for avoiding spring frosts. Pruning late when the sap is flowing helps protect against grapevine trunk diseases – along with other good practices such as avoiding pruning in the rain, trying to always prune upwind and, of course, cleaning secateurs between vines. However, for many vineyards it may not be very practical to leave pruning until the last moment due to workload and labour, unless the vineyard is suited to mechanised pre-pruning,” Greg added.

Sacrificial canes

Losing crop to frost is costly, damaging to production planning, logistics, sales, and winery operations – as well as heart-breaking. Candles, fans, irrigation, and other frost mitigation methods are available, but manipulating the vines architecture by pruning to leave additional buds and sacrificial canes also plays a role.

“I have left sacrificial canes a few times now on sites that are frost prone, including a couple this year, and this has worked well,” explained Joel Jorgensen, Managing Director and Viticulturist, Veraison Ltd. “On the sites that are more frost prone, I prune later, towards the end of February or early March and then tie down the ‘normal’ canes at the end of March – leaving the sacrificial canes upright.

“The principle is that firstly, you are leaving twice as many buds as needed, so that if there is a frost and you lose say, half the buds – you end up with the originally planned bud number. Secondly, by leaving so many buds the vine tends to go through bud burst later – and even a few days can make a difference and avoid a late spring frost.

“Also, because the sacrificial cane is upright, the buds are sitting at a slightly higher night-time temperature, which could be just above the damage point. Although the textbooks might suggest more distinct apical dominance on the upright canes, in my experience, observationally, there is not an obvious difference.”

“Leaving sacrificial canes can save a valuable crop, but it is not without its costs, as tying down after a frost has to be done very carefully to avoid damaging young shoots, it’s a much slower process – and you have to hold your nerve until mid-May! Also tying down in May coincides with many other vineyard tasks. However, at two sites we manage, this pruning technique avoided frost damage and resulted in a potential yield of 9 tonnes per hectare – without leaving the sacrificial canes the frost damage would have seriously reduced or wiped out the yields.

Vine-Works: Leaving sacrifical canes

Respecting the vine

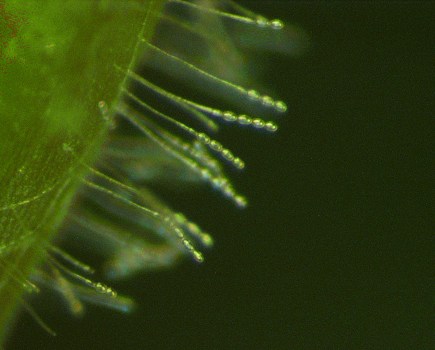

The Simonit&Sirch ‘gentle’ pruning method allows the vine to branch naturally and avoid blocking the flow of sap, or vascular function, allowing for better fertility, resistance to disease and reliable yield.

Joel Jorgensen studied in his native South Africa. “I was taught at university, in Stellenbosch, to prune to respect the plant, and although not described as the Simonit&Sirch method of gentle pruning at the time, it follows many of the same principles, one of which is respect the sap flow,” explained Joel.

“Summer pruning – or shoot selection – needs be carried out in a way to ensure that in the winter you only need to make cuts above the crown. With any cuts made, there needs to be an allowance for dieback, leaving some extra wood to avoid damage to the vascular tissue. By leaving dieback wood, avoiding pruning in the rain or in wet conditions, and if possible, pruning when the sap is rising means that I don’t feel the need to use any wound treatment – but if I did, I would probably select a Trichoderma based product. I think any sealant type product would just trap any infection inside.

The Simonit&Sirch gentle pruning principles are central to Viticulturist Duncan McNeill’s approach to pruning, regardless of whether the vines are VSP, high wire, spur pruned, or cane pruned. “When I adopted the method back in February 2013 it took a little while to re-adjust, but there comes a ‘lightbulb moment’ when the method suddenly makes sense and I’ve never looked back since,” explained Duncan. “It has fundamentally changed the way we make our cuts and how we consider the ramifications of those cuts to the vascular system of the vine. In fact, there are only very minor methodology changes needed to adopt the Simonit&Sirch system – but they have a huge positive impact on the health and longevity of the grapevine,” explained Duncan.

“I’m not concerned about how wide the Y-shaped head may extend. We are in our ninth season now and I don’t have any vines which need re-working. This seems to be a major reservation that people have with the system – there’s no need – you just go with the flow!

“The key is with renewal spurs, and the position of the buds on the spurs. The end bud needs to be facing upwards. This will become next year’s fruit bearing cane. The lower bud needs to be pointing downwards – and this will become next year’s renewal spur. The following year, you simply repeat the process. It is actually very simple and because it has very clear, simple rules I have found it very easy to teach new staff and the quality of my team’s pruning has dramatically improved.

According to Duncan potential yield is influenced by correct pruning as it affects crop loading and vine balance. “If a vine is overloaded with buds, the excess burden of shoots and crop means that distribution of carbohydrates to the other – equally important – organs of the vine is compromised. Foliage and grapes are the primary sinks for carbohydrate – if the vine is overloaded with buds, then there is not enough to be taken into the fruit buds, trunk and root system,” explained Duncan.

“Next year’s buds, the trunk and the roots need this carbohydrate to continue the development of the vine’s permanent structure and to develop the buds for the following year’s crop. I’ve seen so many cases of ‘yo-yo yields’ in vines pruned to double guyot, retaining 20-24 buds, in planting densities of 2.2m x 1m. There are simply too many buds for vines planted this densely – the root system doesn’t have enough soil volume from which to draw moisture to service 20-24 shoots.

“I moved over to all single guyot pruning back in 2015 and have observed far more consistency of yield over recent years. In my opinion, the reason for this is that my vines with 12 shoots can generate enough carbohydrate, via photosynthesis, to ripen a decent crop – with enough left over for distribution to the buds, trunk, and roots. This is vine balance!

Understanding the biology of the vine, its natural growth habits, and internal vascular system are essential – and logical – feels Duncan. “A vine is a creeping plant, so it grows most strongly from its extremities – hence the phenomenon of apical dominance or end point principal. If we load the plant with too many buds, we get exaggerated apically dominant growth.

“We need to understand that every cut will cause a cone of desiccated vascular tissue – with deeper cones of desiccation when cuts are made through older wood. We accept that there will be desiccation at the site of pruning wounds, and this is why we orientate our cuts so that the wounds are made to the upper facing surface of the vine. In doing so, the downwards facing surface of the vine has un-damaged healthy vascular tissue along which to conduct the flow of sap.

“This is also why we only make cuts through older wood once that wood has completely dried out. Cuts through dried out vascular tissue do not cause any further inner desiccation. Therefore, we leave a protective stump when cutting through older wood. As long as there is no shoot growth on the stump next season, no sap is drawn into that stump – and so it dries naturally.

With careful cuts Duncan finds that he has not needed to use any product to protect the pruning wound. “I was taught that leaving protective stumps, which are cut away the following year, is the best method of protection. This makes sense to me – it is working with nature. The pathogenic fungi associated with the Esca disease complex only travel around 2cm per year through the wood. Therefore, if we leave a stump of 3 to 4cm and cut it away the following year, once it’s dried out, this should keep the pathogens out of the ‘living’ inner tissue.

All the tasks we perform in the vineyard are completely inter-related and pruning influences yield, disease risk, vine nutrient status, fruit ripening, wine quality, running costs, longevity – so it’s such an important task to get right,” concluded Duncan.

Training

“Training is an absolute must!” exclaimed Joel. “Pruning needs a good eye, its technical, expensive and can be challenging! “Poor pruning will result in yield losses and unproductive plants – as well as a whole host of other problems. Even though I have been a viticulturist for many years I undertake refresher courses when I can. It’s always good to see how other viticulturists prune – there are so many ways – and if you are not learning, you’re standing still! I offer winter pruning training to groups or individuals, and there are several courses coming up around the regions.